A Cosy Coterie

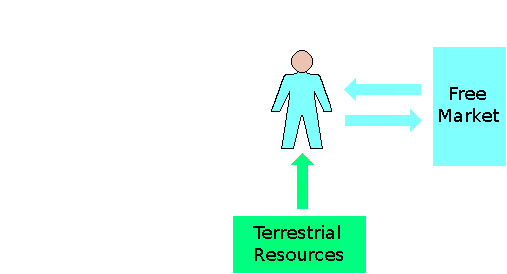

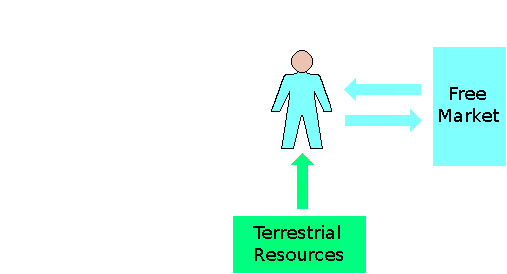

The favoured few, who possess the land and resources of this planet, together form a self-sufficient economy. They do not need anybody else. They own their land and the effective capital it gives them. This provides them with all their needs and luxuries of life all completely free of charge. They thus have free abundance of:

- space to live,

- soil in which to grow their food,

- wood for fuel,

- stone for shelter, plus

- minerals from which to make things.

All they need do is apply their own labour to live, plant, gather, fell, hew and mine as much as they need. These favoured peers can then exchange what they have in excess, for what they want and lack, through their own equitable free market. As a group, they are a self-sufficient self-contained complete economy.

The favoured few own the Earth. But they don't need it all. They can plant, gather, fell, hew and mine all they need from a small fraction of what they own. The remainder of the planet would lie fallow. Nevertheless, it is still theirs. They have the power to allow or forbid anybody else to occupy or use the land they own. This is still abundantly and painfully obvious in the United Kingdom today.

A Source of Labour

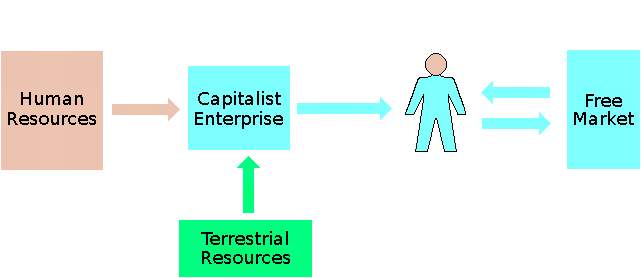

The dispossessed many, on the other hand, have no share of their native planet. They have no land — and hence no space to live, no soil to grow their food, no wood for fuel, no stone for shelter nor minerals from which to make things. Nevertheless, these things are as vital to the dispossessed many as they are to the favoured few. The many can acquire their needs of life from nowhere other than from the few. To be able to do so, however, they must have something to exchange. The only thing they have, which they are able to exchange, is their labour. And to make this exchange is something they are always desperate to do. In other words, labour is always a buyer's market.

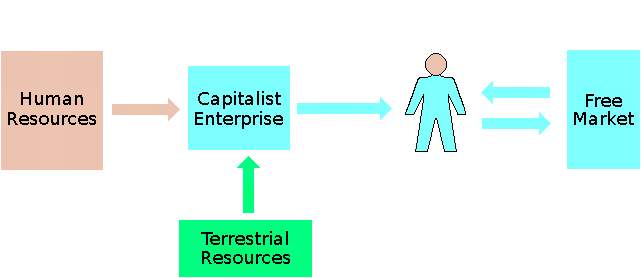

This makes available to the favoured few another economic resource. It provides the only ingredient which, under their primitive self-sufficient economy, the favoured few have to provide themselves; namely, human effort. But this new resource, enables the favoured few to generate their needs and luxuries of life by command rather than by toil. To do this, the favoured few set up enterprises. An enterprise is a process which consumes terrestrial resources and human labour, and produces goods and services for its owner. Its owner may consume these directly or exchange some of them for goods and services produced by his peers via their own private free market.

By using a labour resource far more powerful than his own physical body, each of the favoured few can exploit more of the resources he owns, and thereby generate much greater wealth for himself. When he wants more wealth, all he needs to do is expand his enterprise by hiring more of the dispossessed many to exploit more of his terrestrial resources. When he feels he has sufficient, he may contract his enterprise by laying off as many of his labourers as he no longer needs, returning a corresponding portion of his terrestrial resources to their fallow state. Until he or his descendants require them again.

The dispossessed many are totally dependent on the resource-owning favoured few for all their needs of life, without which they would die. To the favoured few, on the other hand, the dispossessed many are often useful, but never essential. Consequently, with the exception of rare and short-lived periods of rapid economic growth, labour is always a buyer's market. So, all the favoured few need do to command the labour of the dispossessed many is provide them with their basic needs of life: nothing more.

To the favoured few, labourers are simply active resources like machines. Ideally, they would require inputs only while actively generating wealth, being switched off when not in use. Unfortunately, they are not machines: they are biological life-forms. They cannot be switched off completely and switched on again. They still have to be kept alive while idle. They have to be treated like the more sophisticated machines which operate in two modes: active and standby. Such machines consume normal power while active, and a lesser amount while in standby mode. Likewise, labourers must consume a wage while active (employed), and State welfare while idle (unemployed). But nothing more.

Not Profit-Driven

When an enterprise is profiting well, does its owner reward his machines with a bonus? Does he supply them with more electricity? Does he give them extra downtime? Does he reward them with more frequent maintenance? I think not. He wants maximum return from his machines. He therefore supplies them with exactly the electricity they need and no more, whether his profits be high or low. He follows their prescribed maintenance schedules in both the good times and the bad. He keeps their downtime to an absolute minimum irrespective of the state of his business. He supplies them with what they need: no more. To him, machines are a resource for making profit: not for consuming it.

When a farmer has a bumper harvest, does he reward his plough horse? Does he feed it porridge oats instead of bran? Does he bed it down in eider feathers instead of straw? Does he take it on holiday to a rich cool pasture abroad? Does he get another horse so that both can work a shorter week? Does he hire a stable lad to groom it every day? I think not. He feeds it the minimum amount of the cheapest food required to enable it to pull his plough with optimum efficiency: and no more. He beds it in straw irrespective of his harvest. He has a horse to help him produce his harvest: not to help him consume it.

When an enterprise is doing well, does its owner give his labourers a bonus? Does he share his extra profit with them? Does he give them extra holidays? Does he provide for them a more comfortable workplace? Not that I have seen. He wants maximum from his labourers. He pays them what they need in order to function with optimum efficiency as labourers: no more. He keeps their holidays to the same absolute minimum irrespective of his profit. To the owner, labourers are a means for making profit: not consuming it.

This notion of sharing bumper profits must not be confused with the 'bonus + medical care + car' packages that are from time to time built into some employees' contracts. These things are part of the minimum cost of the employee within the market conditions prevailing at the time. Such extras are included only for employees with vital skills that are in short supply at the time. When universities begin to exude a glut of new graduates with the relevant skills, these extra trappings quickly evaporate, as do the high salaries.

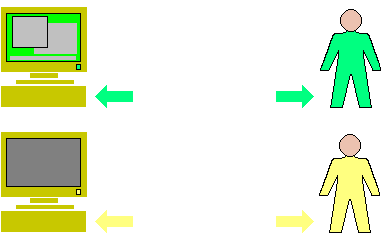

It is the demand for a labourer's skill that drives his wage level: not the profit that the application of his skill generates for his employer. High demand for a skill occurs only during the birth and initial fast growth of the new market or technology to which it applies. Once that new market or technology is established, profits rise, the required skills become abundant, wages fall, bonus employment packages disappear. The profit of the favoured few does not therefore trickle down to the wage packets of those who generate it. There is simply no force or mechanism within the capitalist system to cause it to do so.

Two Distinct Markets

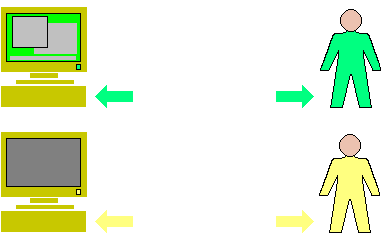

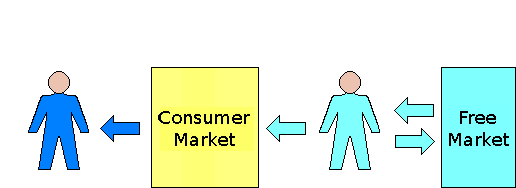

The favoured few can survive and prosper quite well by trading exclusively with their peers all over the world. They form a self-sufficient trading coterie. They do not need the trade or custom of the dispossessed many.

On the other hand, the dispossessed many have needs, but no terrestrial resources with which to produce them. They vitally need food, clothing and shelter. In a capitalist State, the only ones with the resources to produce these things are the favoured few. The dispossessed many cannot survive without these needs, whereas the favoured few do not have to sell to them to survive. Trading in the needs of life is therefore bound forever to be a seller's market.

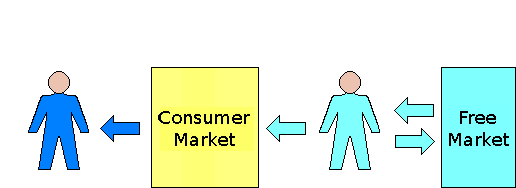

There is no physical fence between them. There is no legal or contractual demarcation between them. Nevertheless, the self-sufficient trading coterie of the favoured few on the one hand, and the consumer market of the dispossessed many on the other hand, are two separate and distinct markets. The first hosts trade between peers whose equal ability to 'take or leave' a deal brings them together as equals. The second is a seller's market. The stronger party gains by selling and loses little by not. The weaker party survives by buying and suffers hardship or death by not.

Far from being vital to the economic needs of the favoured few, the consumer market is merely a bonus which adds to their pleasures.

Parent Document |

©September 1995 Robert John Morton